Ghost

A ghost has been defined as the disembodied spirit or soul of a deceased person,[1] although in popular usage the term refers only to the apparition of such a person.[2] Often described as immaterial and partly transparent, ghosts are reported to haunt particular locations or people that they were associated with in life or at time of death.

Phantom armies, ghost animals, ghost trains and phantom ships have also been reported.[3][4]

Ghosts or similar paranormal entities appear in film, theatre, literature, myths, legends, and some religions.

Contents[hide] |

Terminology

The English word ghost continues Old English gást, hypothetical Common Germanic *gaisto-z. It is common to West Germanic, but lacking in North and East Germanic (the equivalent word in Gothic is ahma, Old Norse has andi m., önd f.). The pre-Germanic form would have been *ghoizdo-z, apparently from a root denoting "fury, anger", cognate to Sanskrit hedas "anger", reflected in Old Norse geisa "to rage". The Germanic word is recorded as masculine only, but likely continues a neuter s-stem. The original meaning of the Germanic word would thus have been an animating principle of the mind, in particular capable of excitation and fury (compare óðr). In Germanic paganism, "Germanic Mercury", and the later Odin, was at the same time the conductor of the dead and the "lord of fury" leading the Wild Hunt.

Besides denoting the human spirit or soul, both of the living and the deceased, the Old English word is used as a synonym of Latin spiritus also in the meaning of "breath, blast" from the earliest (9th century) attestations. It could also denote any good or evil spirit, i.e. angels and demons; the Anglo-Saxon gospel refers to the demonic possession of Matthew 12:43 as se unclæna gast. Also from the Old English period, the word could denote the spirit of God, viz. the "Holy Ghost". The now prevailing sense of "the soul of a deceased person, spoken of as appearing in a visible form" emerges in Middle English (14th century) only.[5]

The synonym spook is a Dutch loanword, akin to Low German spôk (of uncertain etymology); it entered the English language via the United States in the 19th century.[6][7][8][9] Alternate words in modern usage include spectre (from Latin spectrum), the Scottish wraith (of obscure origin), phantom (via French ultimately from Greek phantasma, compare fantasy) and apparition. The term shade in classical mythology translates Greek σκιά,[10] or Latin umbra,[11] in reference to the notion of spirits in the Greek underworld. "Haint" is a synonym for ghost used in regional English of the southern United States[12], and the "haint tale" is a common feature of southern oral and literary tradition.[13] The term poltergeist is a German word, literally a "noisy ghost", for a spirit said to manifest itself by invisibly moving and influencing objects.[14]

The word "ghost" may also refer to any spirit or demon.[2][15][16]

A revenant is a deceased person returning from the dead to haunt the living, either as a disembodied ghost or alternatively as an animated ("undead") corpse. Also related is the concept of a fetch, the visible ghost or spirit of a person yet alive, a notion widespread[citation needed] in shamanistic[citation needed] cultures.

Typology

Anthropological context

A notion of the transcendent, supernatural or numinous, usually involving entities like ghosts, demons or deities, is a cultural universal shared by all human cultures.[17] In pre-literate folk religions, these beliefs are often summarized under animism and ancestor worship.[18]

In many cultures malignant, restless ghosts are distinguished from the more benign spirits which are the subject of ancestor worship.[19]

Ancestor worship typically involves rites intended to prevent revenants, vengeful spirits of the dead, imagined as starving and envious of the living. Strategies for preventing revenants may either include sacrifice, i.e. the provision of the dead with food and drink in order to pacify them, or the magical banishment of the deceased, preventing them from returning by force. Ritual feeding of the dead is performed in traditions like the Chinese Ghost Festival or the Western All Souls' Day. Magical banishment of the dead is present in many of the world's burial customs. The bodies found in many tumuli (kurgan) had been ritually bound before burial,[20] and the custom of binding the dead persists, for example, in rural Anatolia.[21]

Nineteenth-century anthropologist James Frazer stated in his classic work, The Golden Bough, that souls were seen as the creature within that animated the body.[22]

Ghosts and the afterlife

Although the human soul was sometimes symbolically or literally depicted in ancient cultures as a bird or other animal, it was widely held that the soul was an exact reproduction of the body in every feature, even down to clothing the person wore. This is depicted in artwork from various ancient cultures, including such works as the Egyptian Book of the Dead, which shows deceased people in the afterlife appearing much as they did before death, including the style of dress.

Common attributes

Another widespread belief concerning ghosts is that they were composed of a misty, airy, or subtle material. Anthropologists speculate that this may also stem from early beliefs that ghosts were the person within the person, most noticeable in ancient cultures as a person's breath, which upon exhaling in colder climates appears visibly as a white mist.[18] This belief may have also fostered the metaphorical meaning of "breath" in certain languages, such as the Latin spiritus and the Greek pneuma, which by analogy became extended to mean the soul. In the Bible, God is depicted as animating Adam with a breath.

In many traditional accounts, ghosts were often thought to be deceased people looking for vengeance, or imprisoned on earth for bad things they did during life. The appearance of a ghost has often been regarded as an omen or portent of death. Seeing one's own ghostly double or "fetch" is a related omen of death.[23]

White ladies were reported to appear in many rural areas, and supposed to have died tragically or suffered trauma in life. White Lady legends are found around the world. Common to many of them is the theme of losing or being betrayed by a husband or fiancé. They are often associated with an individual family line, as a harbinger of death. When one of these ghosts is seen it indicates that someone in the family is going to die, similar to a banshee.

Legends of ghost ships have existed since the 18th century; most notable of these is the Flying Dutchman. This theme has been used in literature in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Coleridge.

Locale

A place where ghosts are reported is described as haunted, and often seen as being inhabited by spirits of deceased who may have been former residents or were familiar with the property. Supernatural activity inside homes is said to be mainly associated with violent or tragic events in the building's past such as murder, accidental death, or suicide — sometimes in the recent or ancient past. Amongst many cultures and religions it is believed that the essence of a being such as the 'soul' continues to exist. Some philosophical and religious views argue that the 'spirits' of those who have died have not 'passed over' and are trapped inside the property where their memories and energy are strong.

History

Antiquity

King Hsuan (827-783 BC) according to Chinese legend executed his minister, Tu Po, on false charges even after being warned that Tu Po's ghost would seek revenge. Three years later, according to historical chronicles, Tu Po's ghost shot and killed Hsuan with a bow and arrow before an assembly of feudal lords. The Chinese philosopher, Mo Tzu (470-391 BC), is quoted as having commented:

"If from antiquity to the present, and since the beginning of man, there are men who have seen the bodies of ghosts and spirits and heard their voices, how can we say that they do not exist? If none have heard them and none have seen them, then how can we say they do? But those who deny the existence of the spirits say: "Many in the world have heard and seen something of ghosts and spirits. Since they vary in testimony, who are to be accepted as really having heard and seen them?" Mo Tzu said: As we are to rely on what many have jointly seen and what many have jointly heard, the case of Tu Po is to be accepted."[24]

The Hebrew Torah and the Bible contain few references to ghosts, associating spiritism with forbidden occult activities cf. Deuteronomy 18:11. The most notable reference is in the First Book of Samuel (I Samuel 28:7-19 KJV), in which a disguised King Saul has the Witch of Endor summon the spirit of Samuel. In the New Testament, Jesus has to persuade the Disciples that he is not a ghost following the resurrection, Luke 24:37-39 (note that some versions of the Bible, such as the KJV and NKJV, use the term "spirit"). In a similar vein, Jesus' followers at first believe him to be a ghost (spirit) when they see him walking on water.

Ghosts appeared in Homer's Odyssey and Iliad, in which they were described as vanishing "as a vapor, gibbering and whining into the earth." Homer’s ghosts had little interaction with the world of the living. Periodically they were called upon to provide advice or prophecy, but they do not appear to be particularly feared. Ghosts in the classical world often appeared in the form of vapor or smoke, but at other times they were described as being substantial, appearing as they had been at the time of death, complete with the wounds that killed them.[25]

By the 5th century BC, classical Greek ghosts had become haunting, frightening creatures who could work to either good or evil purposes. The spirit of the dead was believed to hover near the resting place of the corpse, and cemeteries were places the living avoided. The dead were to be ritually mourned through public ceremony, sacrifice and libations, or they might return to haunt their families. The ancient Greeks held annual feasts to honor and placate the spirits of the dead, to which the family ghosts were invited, and after which they were “firmly invited to leave until the same time next year”.[26]

The 5th century BC play Oresteia contains one of the first ghosts to appear in a work of fiction.

The ancient Romans believed a ghost could be used to exact revenge on an enemy by scratching a curse on a piece of lead or pottery and placing it into a grave.[27]

Plutarch, in the 1st century AD, described the haunting of the baths at Chaeronea by the ghost of a murdered man. The ghost’s loud and frightful groans caused the people of the town to seal up the doors of the building.[28] Another celebrated account of a haunted house from the ancient classical world is given by Pliny the Younger (c. 50 AD).[29] Pliny describes the haunting of a house in Athens by a ghost bound in chains. The hauntings ceased when the ghost's shackled skeleton was unearthed, and given a proper reburial.[30] The writers Plautus and Lucian also wrote stories about haunted houses.

One of the first persons to express disbelief in ghosts was Lucian of Samosata in the 2nd century AD. In his tale "The Doubter" (circa 150 AD) he relates how Democritus "the learned man from Abdera in Thrace" lived in a tomb outside the city gates in order to prove that cemeteries were not haunted by the spirits of the departed. Lucian relates how he persisted in his disbelief despite practical jokes perpetrated by "some young men of Abdera" who dressed up in black robes with skull masks in order to give him a fright.[31] This account by Lucian notes something about the popular classical expectation of how a ghost should look.

In the 5th century AD, the Christian priest Constantius of Lyon recorded an instance of the recurring theme of the improperly buried dead who come back to haunt the living, and who can only cease their haunting when their bones have been discovered and properly reburied.[32]

Middle Ages

Ghosts reported in medieval Europe tended to fall into two categories: the souls of the dead, or demons. The souls of the dead returned for a specific purpose. Demonic ghosts were those which existed only to torment or tempt the living. The living could tell them apart by demanding their purpose in the name of Jesus Christ. The soul of a dead person would divulge their mission, while a demonic ghost would be banished at the sound of the Holy Name.[33]

Most ghosts were souls assigned to Purgatory, condemned for a specific period to atone for their transgressions in life. Their penance was generally related to their sin. For example, the ghost of a man who had been abusive to his servants was condemned to tear off and swallow bits of his own tongue; the ghost of another man, who had neglected to leave his cloak to the poor, was condemned to wear the cloak, now "heavy as a church tower". These ghosts appeared to the living to ask for prayers to end their suffering. Other dead souls returned to urge the living to confess their sins before their own deaths.[34]

Medieval European ghosts were more substantial than ghosts described in the Victorian age, and there are accounts of ghosts being wrestled with and physically restrained until a priest could arrive to hear its confession. Some were less solid, and could move through walls. Often they were described as paler and sadder versions of the person they had been while alive, and dressed in tattered gray rags. The vast majority of reported sightings were male.[35]

There were some reported cases of ghostly armies, fighting battles at night in the forest, or in the remains of an Iron Age hillfort, as at Wandlebury, near Cambridge, England. Living knights were sometimes challenged to single combat by phantom knights, which vanished when defeated.[36]

From the medieval period an apparition of a ghost is recorded from 1211, at the time of the Albigensian Crusade.[37] Gervase of Tilbury, Marshal of Arles, wrote that the image of Guilhem, a boy recently murdered in the forest, appeared in his cousin's home in Beaucaire, near Avignon. This series of "visits" lasted all of the summer. Through his cousin, who spoke for him, the boy allegedly held conversations with anyone who wished, until the local priest requested to speak to the boy directly, leading to an extended disquisition on theology. The boy narrated the trauma of death and the unhappiness of his fellow souls in Purgatory, and reported that God was most pleased with the ongoing Crusade against the Cathar heretics, launched three years earlier. The time of the Albigensian Crusade in southern France was marked by intense and prolonged warfare, this constant bloodshed and dislocation of populations being the context for these reported visits by the murdered boy.

Haunted houses are featured in the 9th century Arabian Nights (such as the tale of Ali the Cairene and the Haunted House in Baghdad).[38]

Renaissance to Romanticism

Renaissance magic took a revived interest in the occult, including necromancy. The Child ballad Sweet William's Ghost (1868) recounts the story of a ghost returning to beg a woman to free him from his promise to marry her, as he obviously cannot being dead; her refusal would mean his damnation. This reflects a popular British belief that the dead would haunt their lovers if they took up with a new love without some formal release.[39] The Unquiet Grave expresses a belief even more widespread, found in various locations over Europe: ghosts can stem from the excessive grief of the living, whose mourning interferes with the dead's peaceful rest.[40] In many folktales from around the world, the hero arranges for the burial of a dead man. Soon after, he gains a companion who aids him and, in the end, the hero's companion reveals that he is in fact the dead man.[41] Instances of this include the Italian fairy tale Fair Brow and the Swedish The Bird 'Grip'.

Modern period

In 1848, the Fox sisters of Hydesville, New York claimed to have communication with the disembodied spirits of the dead and launched the Spiritualist movement, which claimed many adherents in the nineteenth century.[42]

The rise of Spiritualism saw an increase in popular interest in the supernatural. Books on the supernatural were published for the growing middle class, such as 1852’s Mysteries, by Charles Elliott, which contains “sketches of spirits and spiritual things”, including accounts of the Salem witch trials, the Cock Lane Ghost, and the Rochester Rappings.[43] The Night Side of Nature, by Catherine Crowe, published in 1853, provided definitions and accounts of wraiths, doppelgangers, apparitions and haunted houses.[44] Spiritualist organizations were formed in America and Europe, such as the London Spiritualist Alliance, which published a newspaper called The Light, featuring articles such as “Evenings at Home in Spiritual Séance”, “Ghosts in Africa” and “Chronicles of Spirit Photography”, advertisements for "mesmerists” and patent medicines, and letters from readers about personal contact with ghosts.[45] Mainstream newspapers treated stories of ghosts and haunting as they would any other news story. An account in the Chicago Daily Tribune in 1891, "sufficiently bloody to suit the most fastidious taste", tells of a house believed haunted by the ghosts of three murder victims seeking revenge against their killer’s son, who was eventually driven insane. Many families, “having no faith in ghosts”, thereafter moved into the house, but all soon moved out again.[46]

The claims of spiritualists and others as to the reality of ghosts were investigated by the Society for Psychical Research, founded in London in 1882. The Society set up a Committee on Haunted Houses and a Literary Committee which looked at the literature on the subject.[42] Apparitions of the recently deceased, at the moment of their death, to their friends and relations, were very commonly reported.[47] One celebrated example was the strange appearance of Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon, walking through the drawing room of his family home in Eaton Square, London, looking straight ahead, without exchanging a word to anyone, in front of several guests at a party being given by his wife on 22 June 1893 whilst he was supposed to be in a ship of the Mediterranean Squadron, manoeuvering off the coast of Syria. Subsequently it was reported that he had gone down with his ship, the HMS Victoria, that very same night, after it had collided with the HMS Camperdown following an unexplained and bizarre order to turn the ship in the direction of the other vessel.[48] Such crisis apparitions have received serious study by parapsychologists with various explanations given to account for them, including telepathy, as well as the traditional view that they represent disembodied spirits.[49][50]

Summoning or exorcising the shades of the departed is an item of belief and religious practice for spiritualists and practitioners of ritual magic. The Spiritism of the 19th century has exerted a lasting influence on the Western perception of ghosts. Spiritist séances together with pseudoscientific explanations like ectoplasm and spirit photography appeared to give a quality of scientific method to apparitions. Such approaches to the "paranormal" have become a familiar topos in Western popular culture. The Ghost Club, founded in London in 1862, was an early "ghost hunting" organization.[51] Famous members of the club have included Charles Dickens, Sir William Crookes, Sir William Fletcher Barrett and Harry Price.[51]

According to a poll conducted in 2005 by the Gallup Organization about 32% of Americans "believe in the existence of ghosts."[52]

By culture

European folklore

Belief in ghosts in European folklore is characterized by the recurring fear of "returning" or revenant deceased which may harm the living. This includes the Scandinavian gjenganger, the Romanian strigoi, the Serbian vampir, the Greek vrykolakas, etc. British folklore is particularly notable for its numerous haunted locations.

Popular folklore has always been dismissed as superstition by the educated elite, but belief in the soul and an afterlife remained near universal until the emergence of atheism in the 18th century "Age of Enlightenment." In the 19th century, spiritism resurrected "belief in ghosts" as the object of systematic inquiry, and popular opinion in Western culture remains divided.[53]

Asia

Yūrei (幽霊) are figures in Japanese folklore, analogous to Western legends of ghosts. The name consists of two kanji, 幽 (yū), meaning "faint" or "dim" and 霊 (rei), meaning "soul" or "spirit." Like their Western counterparts, they are thought to be spirits kept from a peaceful afterlife. See also Yokai, Obake.

Ancestor worship is central to Chinese folk religion. Other than the Qingming and Chongyang festivals, descendants should pay tributes to ancestors during the Zhongyuanjie, more commonly known as the Ghost Festival. Traditionally, other than the tombstones or urn-covers, descendants are expected to install altar (神台) in their homes to which they would pay homage regularly in the day, with joss sticks and tea. The ancestors, parents or grandparents, are worshiped or venerated as if they are still living. See also Chinese ghosts, Ghosts in Malay culture, ghost money, Hell bank note.

The Hindu Garuda Purana discusses ghosts.[54] Ghosts in Bengali culture are a recurrent motives both in fairy tales and in modern day Bengali literature as well, references to ghosts may be often found. It is believed that the spirits of those who cannot find peace in the afterlife or die unnatural deaths remain on Earth. The common word for ghosts in Bengali is bhut ( ভূত).

In Central and Northern Asia, Shaman spirit guides play a central role.

Near East and Mediterranean

The Greek underworld (Tartarus) from its Near Eastern templates (compare Hebrew Gehenna and Babylonian Kurnugia), depicts the spirits of the deceased as "shadows" languishing underground. They can be visited by heroes venturing a descent to the underworld, or they can be conjured as apparitions by seers or necromancers. The Christian Hell is a direct continuation of these underworlds. The Greek Hero cult involved the apotheosis of selected individuals after their death.

Ishara was a Near Eastern goddess associated with the underworld. Her name may continue a Proto-Indo-European notion, cognate to Welsh Gwen-hwyfar (Irish Find-abair, from Proto-Celtic *windo-seibaro- "white ghost".

Pre-Columbian Americas

In Aztec mythology, the Cihuateteo were the spirits of human women who died in childbirth. They haunted crossroads at night, stealing children and causing sicknesses, especially seizures and madness, and seducing men to sexual misbehavior.

Depiction in the arts

Ghosts are prominent in the popular cultures of various nations. The ghost story is ubiquitous across all cultures from oral folktales to works of literature.

Renaissance to Romanticism (1500 to 1840)

One of the more recognizable ghosts in English literature is the shade of Hamlet's murdered father in Shakespeare’s The Tragical History of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. In Hamlet, it is the ghost who demands that Prince Hamlet investigate his "murder most foul" and seek revenge upon his usurping uncle, King Claudius. In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the murdered Banquo returns as a ghost to the dismay of the title character.

In English Renaissance theater, ghosts were often depicted in the garb of the living and even in armor, as with the ghost of Hamlet’s father. Armor, being out-of-date by the time of the Rennaissance, gave the stage ghost a sense of antiquity.[55] But the sheeted ghost began to gain ground on stage in the 19th century because an armored ghost could not satisfactorily convey the requisite spookiness: it clanked and creaked, and had to be moved about by complicated pulley systems or elevators. These clanking ghosts being hoisted about the stage became objects of ridicule as they became clichéd stage elements. Ann Jones and Peter Stallybrass, in Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Memory, point out, “In fact, it is as laughter increasingly threatens the Ghost that he starts to be staged not in armor but in some form of 'spirit drapery'.” An interesting observation by Jones and Stallybrass is that

...at the historical point at which ghosts themselves become increasingly implausible, at least to an educated elite, to believe in them at all it seems to be necessary to assert their immateriality, their invisibility. The drapery of ghosts must now, indeed, be as spiritual as the ghosts themselves. This is a striking departure both from the ghosts of the Rennaissance stage and from the Greek and Roman theatrical ghosts upon which that stage drew. The most prominent feature of Rennaissance ghosts is precisely their gross materiality. They appear to us conspicuously clothed.

Ghosts figured prominently in traditional British ballads of the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly the “Border Ballads” of the turbulent border country between England and Scotland. Ballads of this type include The Unquiet Grave, The Wife of Usher's Well, and Sweet William's Ghost, which feature the recurring theme of returning dead lovers or children. In the ballad King Henry, a particularly ravenous ghost devours the king’s horse and hounds before forcing the king into bed. The king then awakens to find the ghost transformed into a beautiful woman.[56]

One of the key early appearances by ghosts in a gothic tale was The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole in 1764.[57]

Washington Irving's short story The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820), based on an earlier German folktale, features a Headless Horseman. It has been adapted for film and television many times, most notably in Sleepy Hollow, a successful 1999 feature film.[58]

Victorian/Edwardian (1840 to 1920)

The “classic” ghost story arose during the Victorian period, and included authors such as M. R. James, Sheridan Le Fanu, Violet Hunt, and Henry James. Classic ghost stories were influenced by the gothic fiction tradition, and contain elements of folklore and psychology. M. R. James summed up the essential elements of a ghost story as, “Malevolence and terror, the glare of evil faces, ‘the stony grin of unearthly malice', pursuing forms in darkness, and 'long-drawn, distant screams', are all in place, and so is a modicum of blood, shed with deliberation and carefully husbanded...”[59]

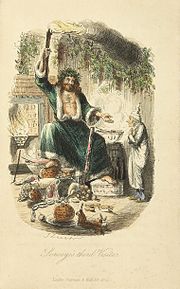

Famous literary apparitions from this period are the ghosts of A Christmas Carol, in which Ebenezer Scrooge is helped to see the error of his ways by the ghost of his former colleague Jacob Marley, and the ghosts of Christmas Past, Christmas Present and Christmas Yet to Come.

Oscar Wilde's comedy The Canterville Ghost has been adapted for film and television on several occasions. Henry James's The Turn of the Screw has also appeared in a number of adaptations, notably the film The Innocents and Benjamin Britten's opera The Turn of the Screw.

Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things is a 1904 collection of Japanese ghost stories collected by Lafcadio Hearn, and later made into a film.

In the United States during the years prior to and during the First World War, folklorists Olive Dame Campbell and Cecil Sharp collected ballads from the people of the Appalachian Mountains which included ghostly themes, such as The Wife of Usher's Well, The Suffolk Miracle, The Unquiet Grave, and The Cruel Ship's Carpenter. The theme of these ballads was often the return of a dead lover. These songs were variants of traditional British ballads handed down by generations of mountaineers descended from the people of the Anglo-Scottish border region.[60]

Modern Era (1920 to 1970)

Professional parapsychologists and “ghosts hunters”, such as Harry Price and Peter Underwood, published accounts of their experiences with ostensibly true ghost stories such as The Most Haunted House in England, and Ghosts of Borley.

Children’s benevolent ghost stories became popular, such as Casper the Friendly Ghost, created in the 1930s and appearing in comics, animated cartoons, and eventually a 1995 feature film.

Noël Coward's play Blithe Spirit, later made into a film, places a more humorous slant on the phenomenon of haunting of individuals and specific locations.

With the advent of motion pictures and television, screen depictions of ghosts became common, and spanned a variety of genres; the works of Shakespeare, Dickens and Wilde have all been made into cinematic versions. Novel-length tales have been difficult to adapt to cinema, although that of The Haunting of Hill House to The Haunting in 1963 is an exception.[57]

Sentimental depictions during this period were more popular in cinema than horror, and include the 1947 film The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, which was later adapted to television with a successful 1968-70 TV series.[57] Genuine psychological horror films from this period include 1944's The Uninvited, 1945's Dead of Night.

Post-modern (1970-present)

The 1970s saw screen depictions of ghosts diverge into distinct genres of the romantic and horror. A common theme in the romantic genre from this period is the ghost as a benign guide or messenger, often with unfinished business, such as 1989's Field of Dreams, the 1990 film Ghost, and the 1993 comedy Heart and Souls.[61] In the horror genre, 1980's The Fog, and the A Nightmare on Elm Street series of films from the 1980s and 1990s are notable examples of the trend for the merging of ghost stories with scenes of physical violence.[57]

Popularised in such films as the 1984 comedy Ghostbusters, ghost hunting became a hobby for many who formed ghost hunting societies to explore reportedly haunted places. The ghost hunting theme has been featured in reality television series, such as Ghost Hunters, Ghost Hunters International, Most Haunted, and A Haunting. It is also represented in children's television by such programs as The Ghost Hunter and Ghost Trackers. Ghost hunting also gave rise to multiple guidebooks to haunted locations, and ghost hunting “how-to” manuals.

The 1990s saw a return to classic “gothic” ghosts, whose dangers were more psychological than physical. Examples of films from this period include 1999’s The Sixth Sense, and 2001’s The Others.

Asian cinema has been adept at producing horror films about ghosts, such as the 1998 Japanese film Ringu (remade in America as The Ring in 2002), and the Pang brothers' 2002 film The Eye.[62]

Scientific explanations

| This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. Please improve this section if you can. (February 2009) |

Some researchers, such as Professor Michael Persinger (Laurentian University, Canada), have speculated that changes in geomagnetic fields (created, e.g., by tectonic stresses in the Earth's crust or solar activity) could stimulate the brain's temporal lobes and produce many of the experiences associated with hauntings. This theory has been tested in various ways. Some scientists have examined the relationship between the time of onset of unusual phenomena in allegedly haunted locations and any sudden increases in global geomagnetic activity. Others have investigated whether the location of alleged hauntings is associated with certain types of magnetic activity. Finally, a third strand of work has involved laboratory studies in which stimulation of the temporal lobe with transcerebral magnetic fields has elicited subjective experiences that strongly parallel phenomena associated with hauntings. All of this work is controversial; it has attracted a large amount of debate and disagreement.[63] Sound is thought to be another cause of supposed sightings. Frequencies lower than 20 hertz are called infrasound and are normally inaudible, but scientists Richard Lord and Richard Wiseman have concluded that infrasound can cause humans to experience bizarre feelings in a room, such as anxiety, extreme sorrow, a feeling of being watched, or even the chills.[64] Carbon monoxide poisoning, which can cause changes in perception of the visual and auditory systems,[65] was recognized as a possible explanation for haunted houses as early as 1921.

According to the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, to date, there is no credible scientific evidence that any location is inhabited by spirits of the dead.[66]

Critics of "eyewitness ghost sightings" suggest that limitations of human perception and ordinary physical explanations can account for such sightings; for example, air pressure changes in a home causing doors to slam, or lights from a passing car are reflected through a window at night.[67] Pareidolia, an innate tendency to recognize patterns in random perceptions, is what some skeptics believe causes people to believe that they have seen ghosts.[68] Reports of ghosts "seen out of the corner of the eye" may be accounted for by the sensitivity of human peripheral vision. According to skeptical investigator Joe Nickell:

...peripheral vision is very sensitive and can easily mislead, especially late at night, when the brain is tired and more likely to misinterpret sights and sounds.[67]

Nickell also states that a person's belief that a location is haunted may cause them to interpret mundane events as confirmations of a haunting:

Once the idea of a ghost appears in a household . . . no longer is an object merely mislaid. . . . There gets to be a dynamic in a place where the idea that it's haunted takes on a life of its own. One-of-a-kind quirks that could never be repeated all become further evidence of the haunting.[67]

This December i will cellebrate hellowen days, with my birthday party... it's will be fun... have scary party....

ReplyDeleteThank for info... now i more know about meaning of hellowen